Gathering wild foods in Nebraska is not just a spring, summer or fall outdoor activity, it can be done in winter.

What? Winter! Seriously. Don’t stop reading. Stay with me here.

But let’s get this straight: Foraging for wild plant foods in winter is not easy. It’s tough, it’s rough, it’s cold, it’s hard work. It’s challenging, to say the least. Frigid temperatures, snow cover and low-light add to the difficulty. Winter foraging can sometimes be about slim-pickings, too. However, if you have basic knowledge of specific plants, bundle up and put forth the effort to find and correctly harvest them, you’ll enjoy a variety of nutritious, natural foods, from greens to nuts to roots to fruits, even during the snowiest, coldest parts of winter in Nebraska.

Here’s the other thing, and it’s a big thing: By knowing what plants to gather, prepare and eat in a winter outdoor survival situation, you may be able to save your life!

So let’s get to it.

DISCLAIMER: Remember, when harvesting wild foods of any kind: Check regulations, have landowner permission, positively identify the plant or part thereof by using a good, reputable field guide or app or by going with a master naturalist, learn about any poisonous lookalikes in your area, do not collect near roads, parking lots or other potentially polluted places, and eat only small amounts of wild foods that are new to you, and harvest in a sustainable manner never taking more than you can eat or over 5% of a plant population. If there are any doubts about a particular plant, don’t eat it.

EQUIPMENT NEEDED: Among the equipment needed for collecting wild edible plants in winter: Warm clothing, insulated or neoprene hip waders or waterproof boots, heavy duty-insulated rubber gloves, kitchen shears or pocket knife, small hand rake, one-gallon plastic Ziploc bags and a 5-gallon plastic bucket.

THE EDIBLES: Here are seven reliable wild winter edibles that you can find in the Cornhusker State.

(1) Cattails (roots and shoots).

Known as the “supermarket of the swamp,” the cattail is a highly versatile wild edible and survival food. The young cob-like tips of the wetland plant are edible as is the white bottom of the stalk, spurs off the main roots and spaghetti like rootlets off the main roots. They have vitamins A, B, and C, potassium and phosphorus. Cattail roots contain a white starch that is 150 calories per cup, and the shoots are also quite edible, bringing in about 50 calories per cup and a touch of Vitamin K. Historically, the Pawnee Native American Tribe knew the value of cattails growing along Nebraska streams and marshes and utilized them as a food source. The pollen of cattails is edible, too, as are the sprouts that grow on the roots. The cattail plant is topped with a seed head that looks very much like a corn dog in size and shape. Keep in mind that it is not the fuzzy characteristic flower heads that you want to eat, but rather, the rhizomes and lower stalks. The fibrous part of the root must be removed though, as it may cause severe stomach upset. Cattail rhizomes are starchy and sweet, with an immensely mild flavor and scent, and they’re packed with vitamin C, potassium and phosphorous. To prepare, gather your winter cattail roots/shoots and pull off the tough/fibrous outer leaves and material until you reach the tender white inner core of the cattail heart. Wash the heart thoroughly and cut into roughly 4-inch pieces. Put a healthy amount of high-heat cooking oil in the bottom of your skillet. Cook for about 3 minutes. In the cooking process, add minced garlic, minced ginger and a few splashes of sesame seed oil. Then, cover and let cook for about one minute. They taste somewhat similar to potatoes. Serve. Enjoy!

(2) Water Cress.

While stream side seeking cattails, keep an eye out for watercress, a plant that likes cold water. It’s a peppery member of the mustard family. Often found in winter streams, it can be a flavoring and/or a green to put into soups. More palatable than supermarket watercress, wild watercress actually tastes sweeter in the wintertime. Even during the snowiest days of winter, watercress can be found growing in tight, bright green bunches near water, particularly at springs or in spring-fed streams in Nebraska. This delicate vegetable is quite tasty raw, whether added to salads or used as a garnish on sandwiches. Consume it quickly after picking it, and always be sure to only pick it from bodies of water that aren’t compromised by runoff pollutants.

(3) Rose Hips.

Rose hips provide welcome bursts of color in Nebraska’s wintry countryside, especially in the Sandhills region. They’re also full of sweet pulp that can be eaten raw or boiled down for syrup, jam or tea. Rose hips have sort of an herbal flavor that’s suggestive of roses without tasting floral. Just boil 12-15 of them for 3-5 minutes, smash them open with a spoon and let them steep for 20 minutes. Strain and serve. The tangy, sweet, red-colored fruits of wild rose bushes come in at 162 calories per cup. They’re an extremely good source of Vitamin E, Vitamin K, calcium, and magnesium, as well as a powerful source of dietary fiber, Vitamin A and manganese. They are also a Vitamin C powerhouse containing 7 times your daily dose. To avoid getting the wrong fruit or berry, look for compound leaves and thorns on the rose bushes. The red rose hips should also be branching upward, not dangling fruits.

(4) Pine Needles.

The tea extracted from pine needles is tasty, easy to make and very high in vitamin C, making it a great remedy for the common cold. The obvious trees in winter to look to for food are the conifers. Pine, spruce, fir, tamarack and hemlock all have high levels of vitamin C. Also remember that the juniper is a conifer and many have berries throughout the winter. Most pine and spruce trees (there are many sub-species) contain beta carotene. The juniper contains vitamins A, B1, B2, B3, C, calcium, chromium, cobalt, iron, magnesium, manganese and phosphorus. It also contains vitamin A and beta-carotene. While most varieties of pine are safe, always be absolutely certain that you don’t harvest the needles from Ponderosa Pine, Yew or Norfolk Island pine, all of which are poisonous.

(5) Acorns.

Acorns have been called the ultimate survival food. They are packed with fats and nutrition. Along with black walnuts, pecans, hickories, hazelnuts, beechnuts and pine nuts, acorns can be gathered from the ground. Separate out all of the shell fragments and place the nut meat in a pot of warm water. Soak them in warm water for several hours, then pour off the water. This removes the irritating, bitter, astringent-tasting tannin they contain. One of the easiest ways to cook acorns is to roast them. Place the damp nut chunks on a baking sheet and sprinkle with fine salt or sea salt. Toast them for about 15-20 minutes at 375 degrees in a preheated oven, or roll them around in a dry frying pan over a camp fire. You will be able to tell when they are done when their color changes a bit, and the nut pieces smell like roasted nuts! Eat them out of your hand like peanuts.

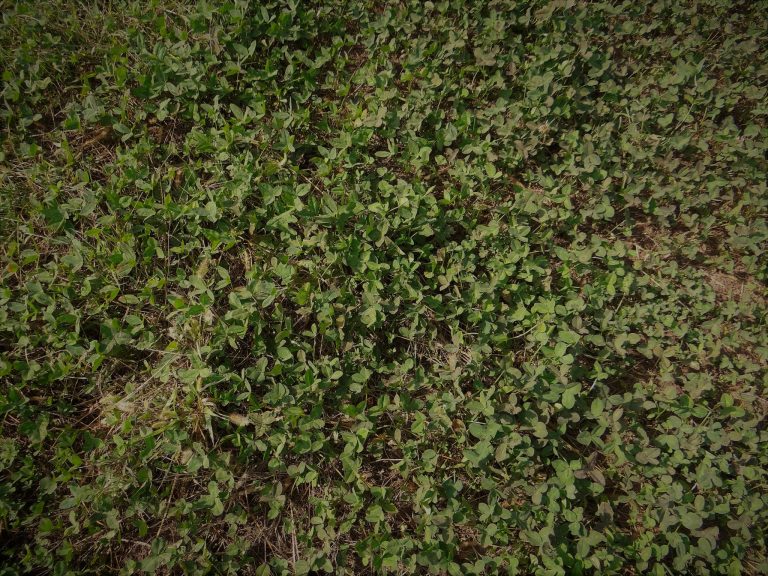

(6) Clover.

Clover, a legume, is a widespread plant that retains its green color throughout the winter. You can spot clover by their distinctive trefoil leaflets. Those clover leaflets are edible and pleasant to eat as they have kind of a faint bean-like flavor. They can be tossed into a salad or added to soups, stews and other dishes such as lasagna. The preferable part of this wild edible is the flower. Red clover is the tastiest of all clovers but be sure to go easy on the intake! You can eat clovers raw but they taste better boiled. Even though these are safe to eat, if you go overboard you may experience bloating and gas. For this reason, clovers should not be consumed by women who are pregnant or by nursing mothers. This incredible plant is a source of many nutrients including vitamins A, B1, B2, B3 and C. It also contains calcium, chromium, cobalt, magnesium, manganese, phosphorous, potassium, selenium, silicon, sodium, and zinc. Clovers are also a good source of protein, fat, as well as crude and dietary fiber.

(7) Persimmon.

One of the most cold-hardy fruits in Nebraska is that of the American Persimmon tree. When ripe, the fruit of this native hardwood is round and about one to two inches in diameter, ranges in color from a yellow-orange to a dark red-orange, and contains a large seed. To be palatable, the wild persimmon fruit needs to be a bit wrinkled, soft, squishy and sort of sticky. The completely ripe persimmon fruits are truly a naturally sweet delicacy. Per one cup of persimmon fruit pulp, there is 127 calories and a full day’s requirement of vitamin C. You can eat ripe persimmons fresh, picked directly from the plant, if desired, or make them into a sweet jelly, jam or pudding. Interestingly, after the leaves of the persimmon tree have dropped, much of the fruit will still remain attached to the branches in winter. They are still edible, and you can even pick them up off the ground for consumption after you look them over. Be sure they are not rotten or half-eaten by wildlife. There are stories of early prairie pioneers in Nebraska gathering persimmon fruits in the wintertime when other foods and even wild game animals were hard to find.

Get more information on a couple other winter wild edibles in Nebraska by clicking here.

“We walk on trails and look at scenery without knowing anything about the flora and fauna surrounding us, let alone how to utilize it in a way that would allow one to live in the forest for any length of time.” — Sam Larson, Wilderness Skills Instructor.

The post Foraging for Winter Wild Edibles in Nebraska appeared first on Nebraskaland Magazine.