Nature’s Abstract Art

Enlarge

Photos and story by Gerry Steinauer

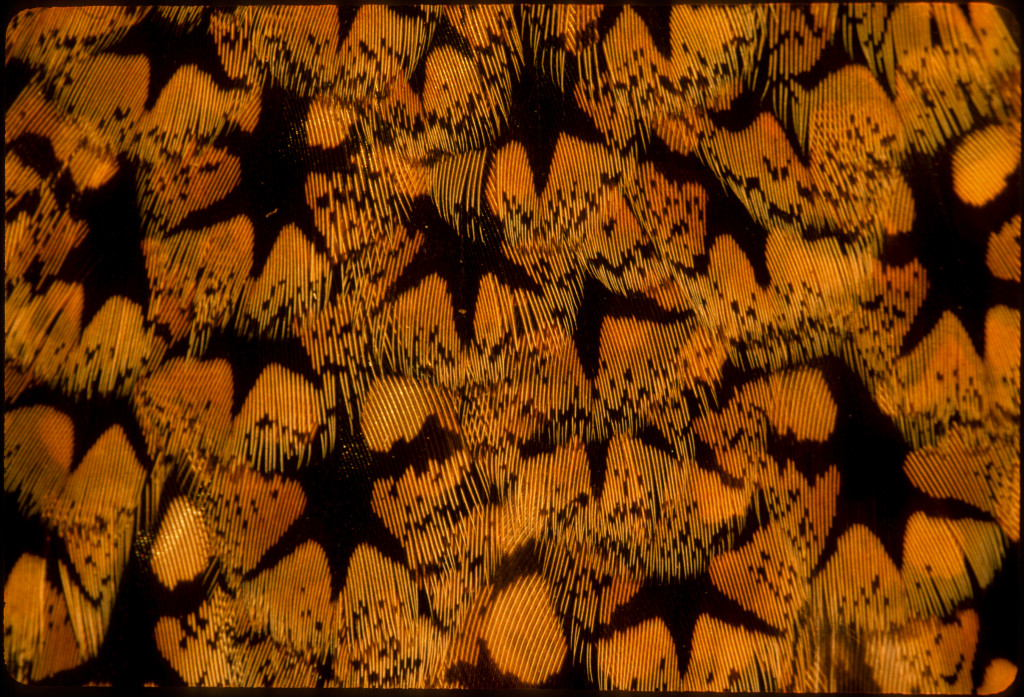

About 20 years ago on a Sandhills hunt, I was arranging a few harvested grouse for a classic “I shot my limit” photo when I noticed something far more enticing — the feathers on the bird’s back accentuated in warm sunlight. After taking the photo, I was immediately hooked and have been photographing feather close-ups whenever the opportunity arises.

For bird hunters, feathers to photograph are easy to come by. Gaudy rooster pheasants are decked out in an array of feather colors and patterns, and waterfowl, prairie chickens, sharp-tailed grouse, quail and turkeys each have a unique plumage.

Non-hunters seeking feathers need not fret: Ask a friend to save you the plumage of their harvested birds, which can be easily preserved and photographed later. I stretch and pin the skins of fresh-cleaned birds, feather side down, to cardboard. Then I sprinkle borax on them and rub it into any remaining flesh or fat on the skin. Two weeks later, shake off the borax, and the preserved, odorless plumage is ready for a photo shoot.

Though illegal to possess non-game, native birds, such as cardinals or robins, or their feathers, I photograph these in place when finding recently deceased birds. For example, the unfortunate blue jay that flew into our picture window became an ideal candidate. Single feathers, say from the wing of a sandhill crane or tail of a yellow-shafted flicker or tom turkey, gracefully perched in nature, are also photogenic.

I photograph feathers in the early morning or evening, when low-angle sunlight best refracts iridescent colors from the feathers and long shadows can add interesting detail (see page 27 for more on refracted colors). If needed, I use a lens brush to smooth the feathers and remove distracting flecks of dried skin or other debris. In my backyard, I place the bird or feathered skin on a low stump and shoot from a tripod using a 105 mm macro lens. Since the feathers are stationary, I usually use a smaller aperture for greater depth of field and a low ISO. The latter provides more detail and color saturation and less noise, which makes for a better print, especially at large scale.

With intricate designs and iridescent colors, feather photographs can approach the abstract. Hanging on your wall, your photos might leave your sophisticated friends asking, “That’s cool. Is it a Richter? A Pollock?” ■

Feather Biology

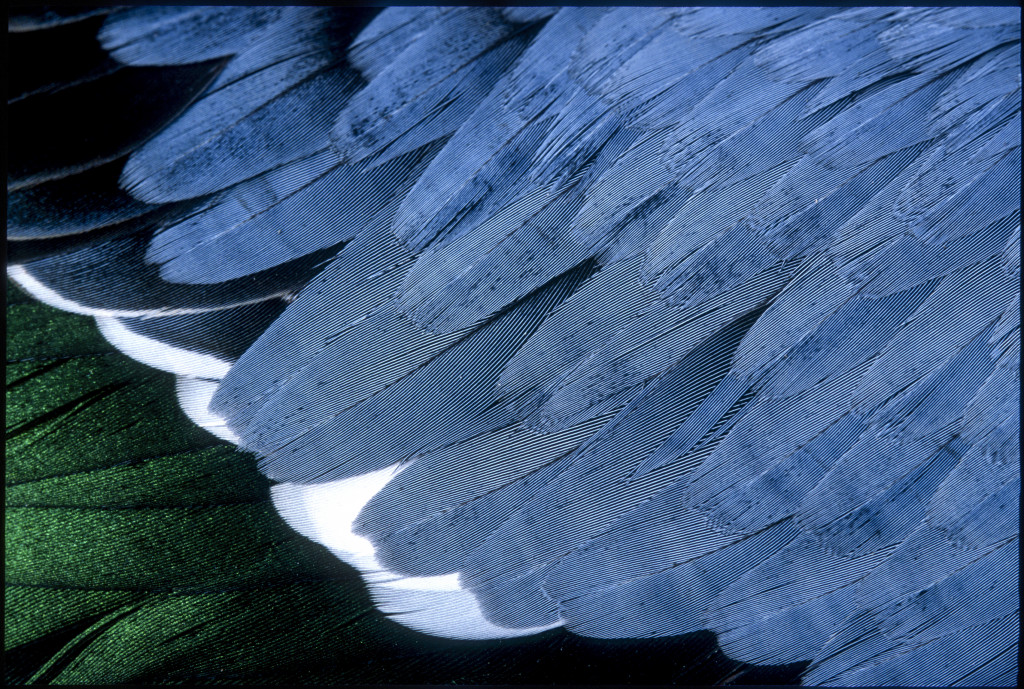

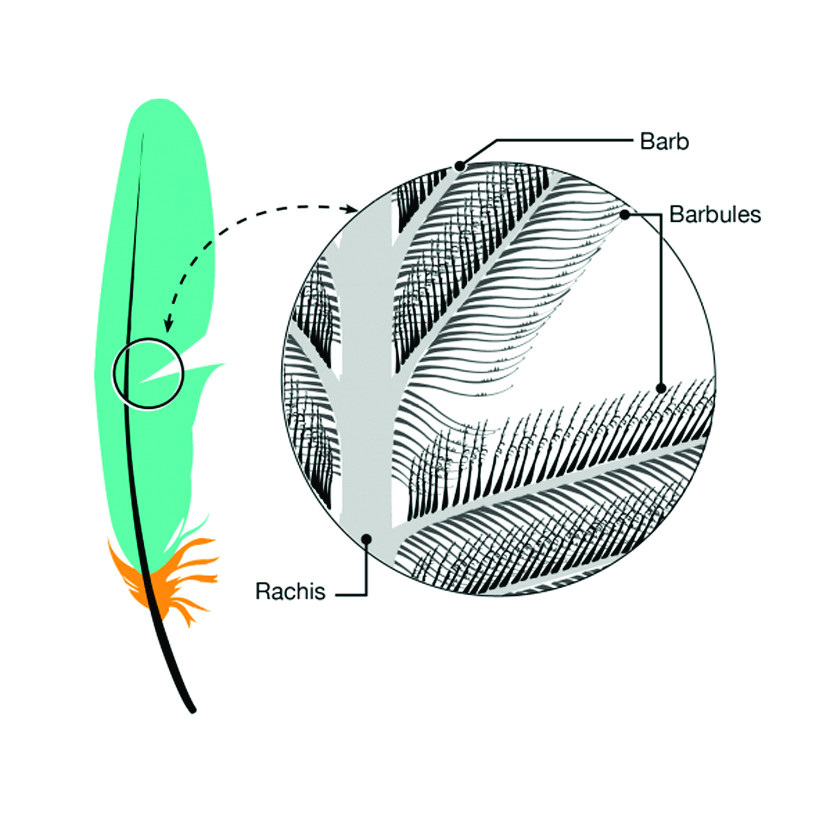

Feathers are an engineering marvel. Composed of the protein beta-keratin, they have a central rachis (stem) that branches into barbs and then barbules. The latter have hooklets that interlock, like Velcro, with nearby barbules. Modifications in the branching pattern allow feathers to serve a variety of functions.

Fluffy down feathers have flexible barbs and long barbules that trap air and insulate birds. Baby ducks, for instance, are born with a complete coating of natal down to protect against cold air and water. Due to their tightly interlocking barbules, long wing feathers are stiff, flat and air-proof — allowing birds to fly. They are also anchored to wing bones by ligaments for precise maneuverability and strength. Bristles, often consisting of only a stiff rachis, are the simplest feathers. These frequently occur on the head where they serve as protection or are uniquely colored or shaped for display.

Academy. Allaboutbirds.org

Recent fossil finds in China suggest the first feathers appeared about 250 million years ago in reptile ancestors of the dinosaurs. The early dinosaurs likely had simple feathers composed of hollow tubes, which served to insulate and, if colored, to show off or camouflage the warm-blooded creatures.

Feathers further evolved during the age of dinosaurs. The tubes formed into clusters of barbs, the base of these then fused to form the rachis. Eventually barbules and hooklets developed. Archaeopteryx, evolved from a small flying dinosaur about 150 million years ago and believed to be the first bird, arrived to the party decked out in a diversity of feather types.

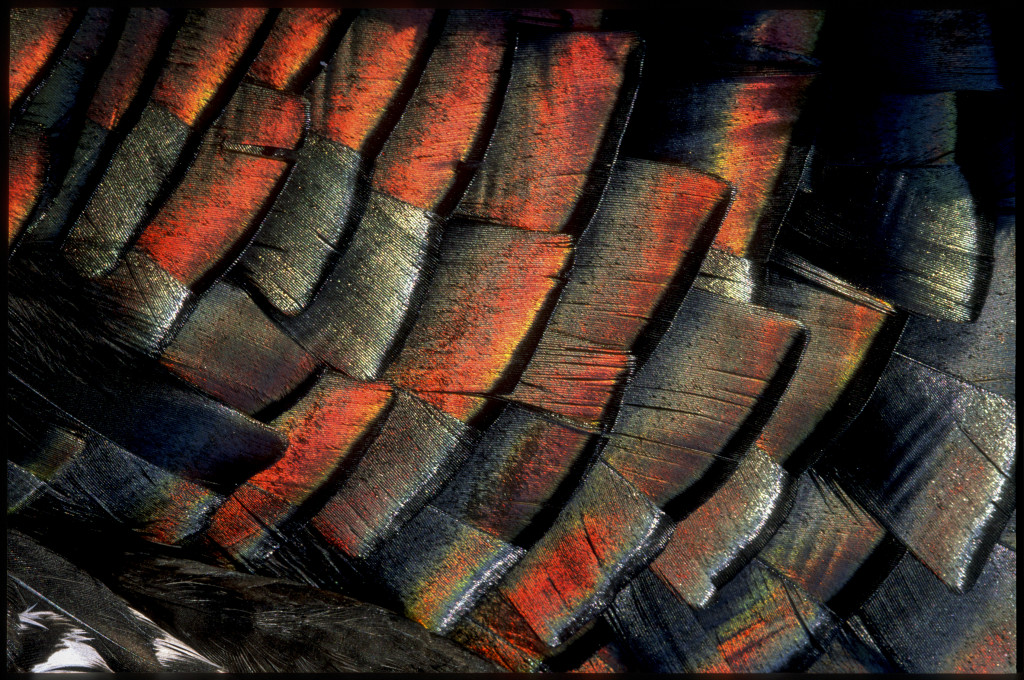

Feather Colors

Earth’s 10,000-plus bird species are decorated in an assortment of colors that are formed in two primary ways: various pigments in a feather reflect specific colors of light, or a feather’s structure refracts specific colors. Reflection is when light bounces off an object, such as a mirror or pigment, whereas refraction is when light is bent when passing through an object, such as a prism or a feather’s barbules, producing shifting iridescent colors. Feather color sometimes results from a combination of reflection and refraction.

Pigments are colored substances found in both plants and animals. In feathers, they consist mainly of carotenoids, melanin and porphyrins. Carotenoids reflect red and bright yellow-colored light, melanin reflects pale yellows, browns and black, while porphyrins reflect a wide range of colors including pinks, reds, browns and greens.

The iridescent colors of many birds, such as hummingbirds, are a result of the refraction of incoming sunlight by the microscopic structure of the barbules. Refraction works like a prism, splitting the incoming light into its component colors, such as reds, yellows and greens. As the viewing angle of the eye or camera lens to a prism or feather changes, it sees different components of this color spectrum — a shifting array of iridescent colors.

In the below photo, the normally black turkey breast feathers appear red and silver not because of camera trickery or Photoshop, but due to refraction of the sunlight by the barbules into its component colors. A simple shift of the lens angle captured these colors.

The post Feathers: Nature’s Abstract Art appeared first on Nebraskaland Magazine.