Enlarge

Photo by Eric Fowler

By Eric Fowler

Were it not for happenstance, we might know little about Lt. Gabriel Field. When John “Jack” Rathjen uncovered a portion of his headstone while plowing a crop field in 1954, it led to the exhumation of six graves, including Field’s, north of where Fort Atkinson, the first U.S. military fort in what was to become Nebraska, had once stood.

In the years that followed, historians, both professionals and amateurs, searched through military and genealogical records trying to answer the obvious question: Who was Gabriel Field? They uncovered many details about the life and military career of Field, the soldier who helped build Fort Atkinson and met his untimely death there in 1823 that, were it not for a farmer’s plow, might remain footnotes in history.

On April 16, the 200th anniversary of his death, Field will return to Fort Atkinson, where his remains will be reburied in the Monument to the Deceased, an event that will fulfill the wishes of the man who found his headstone.

The Soldier

Gabriel Field was born near Louisville, Kentucky, in 1794 or 1795, according to research by Gayle Carlson, an archeologist with History Nebraska, formerly the Nebraska State Historical Society, who spent years researching the soldier. His parents, Abner Field and Jane Pope, had moved there from Virginia, where they were well-known and influential. Maj. Abner Field was a commander in the Revolutionary War and senator in Virginia. Pope came from an aristocratic family. Among Field’s distant relatives were two presidents, George Washington and, through marriage, John Quincy Adams, as well as one of the country’s most famous explorers, William Clark.

Field gained military experience in the War of 1812, serving in the Kentucky Volunteers and Kentucky Militia. After the war, he worked as a field surveyor in northwestern Missouri in 1815 and 1816.

In May 1817, he sought and received a commission as a second lieutenant in the Army’s Rifle Regiment. In 1818, the regiment was assigned to the Yellowstone Expedition. Under the command of Col. Henry Atkinson, the expedition was to establish a series of forts along the Missouri River between St. Louis and the mouth of the Yellowstone River in Montana to protect the growing fur trade and prevent British encroachment from the north. In all, it included 1,126 members of the Rifle Regiment and Infantry, one fourth of the young nation’s army.

Field, having been promoted to first lieutenant, was one of 10 officers to lead 347 enlisted men of the First Battalion of the Rifle Regiment, under the command of Col. Talbot Chambers, up the Missouri River as an advance party of the Yellowstone Expedition. According to the journals of John Gale, the surgeon with the regiment, they left Fort Belle Fontaine near St. Louis on August 30. Just as members of the Lewis & Clark Expedition had done nearly 20 years earlier, they rowed, poled and pulled 10 keelboats up the river. They made it as far as Cow Island, north of present-day Weston, Missouri, where they made winter camp on October 18, having traveled more than 360 miles in 50 days. They remained there, awaiting the arrival of Atkinson and the rest of the expedition, which wouldn’t set out from Belle Fontaine until July 4, 1819.

That winter, Field led or was part of several parties that explored the region, visiting a Kansas Indian village, and tracing the Platte and Nodaway rivers in Missouri. The following spring, he led a party to Manual Lisa’s trading post just north of present-day Omaha and was to remain there until the battalion arrived. He apparently went farther, advancing to Council Bluff, the hill overlooking the Missouri River on the east edge of present-day Fort Calhoun, where Lewis and Clark held council with the Oto and Missouria Indians in 1804 and a site Clark identified in his journals as a good location for a trading establishment. On August 16, Gale wrote that Field “arrived from Council Bluff destitute of subsistence,” with no explanation as to why he returned to Cow Island.

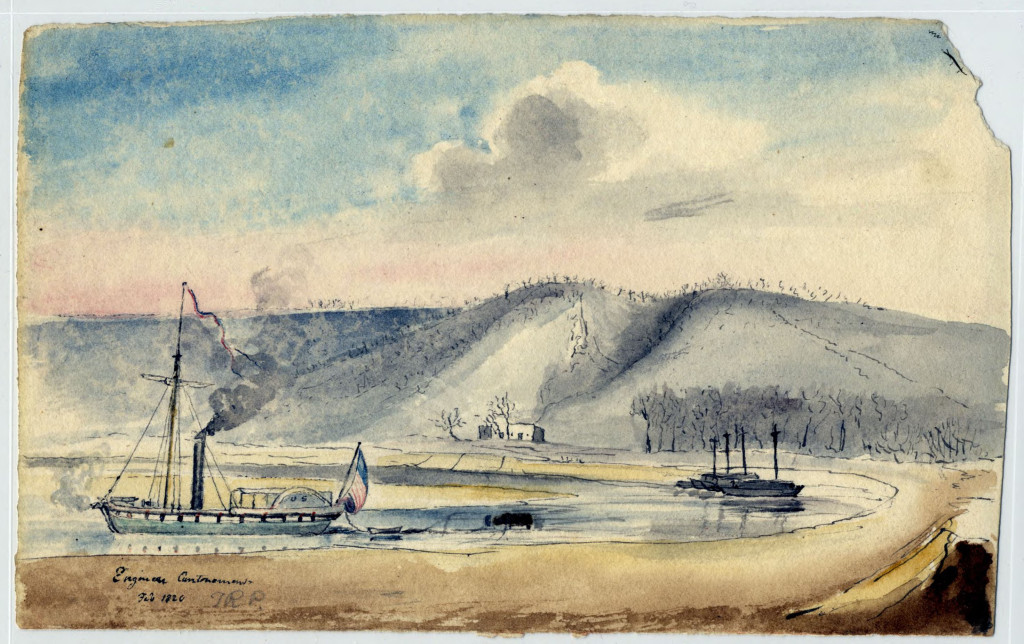

Atkinson and his troops left Fort Belle Fontaine in three steamboats loaded with supplies. The crafts, still in their infancy, weren’t able to navigate the snags, sandbars and current of the river and were left behind, leaving troops to transport supplies in keelboats and barges. A fourth steamboat, carrying the smaller scientific and exploration party of the expedition and led by Maj. Stephen Long, made it to Cow Island. Field and a party of soldiers in a keelboat accompanied Long as he continued north, setting up winter camp, Engineer Cantonment, just north Manuel Lisa’s Post. The rest of the soldiers continued north, arriving between late September and early October at what would be their winter camp, Cantonment Missouri, on the banks of the river two miles north of Council Bluff. This was well short of their intended goal of reaching the Mandan Indian Villages in central North Dakota.

The excruciating work took its toll on the troops. “Nearly every man had suffered severely from sickness, and many experienced relapses, before arriving at our point of destination; nor did we then cease to suffer from dysentery, catarrh and rheumatism,” Gale wrote in his journals.

While the exhausted troops took to building winter quarters, Field was given another assignment. With his background as a surveyor, he was to plot a course from Council Bluff to the location of the nearest post office near present day Brunswick, Missouri. With 10 enlisted men on horseback, he completed the task in 28 days, crossing what Field estimated to be 340 miles of what was then the Missouri Territory.

Field described the route, which he dubbed Field’s Trace, in his journal, the original copy of which now resides in the National Archives in Washington, D.C. In it, he writes often of the expansive prairie that stretched for miles, the woodlands and rich soil they traversed. He mentions several times crossing trails made by Native Americans that had been recently traveled and meeting a band of Iowa Indians. He named each of the 60 streams they crossed, including Elk Creek, where their hunter killed the first elk on the route. “The Country here is more abundant in game than any we have passed through, which is in consequence of their having more shelters to cover them from pursuit,” Field wrote.

Surveying the route was a difficult task, but things didn’t get easier when the party returned to Camp Missouri. It would be January before the quarters were nearly completed, and it was a cold winter. The expedition wasn’t sufficiently supplied, and many of the food supplies had spoiled. Subsisting on salted and smoke-dried meat, and lacking vegetables and fruit and vitamin C, scurvy first appeared in the camp in late January. By February, most were affected, and it wasn’t until April, when natives showed them wild vegetables, such as wild onion, that had begun to sprout that the troops recovered. The malady had taken its toll, though, claiming more than 160 soldiers. Studies of Field’s remains showed he was one of hundreds who survived scurvy.

Due to the lack of progress and high cost, congress halted the Yellowstone Expedition, and instead ordered Long to explore the Platte River west to the Rocky Mountains. Atkinson’s troops remained, but flooding inundated Camp Missouri, forcing them to relocate to high ground on Council Bluff. There, they built a fort that in 1821 would be named for their commander, Atkinson, who had been promoted to general and moved on, replaced by Col. Henry Leavenworth.

That fall, Field went to back to work on the Trace, making some corrections in the course to make it easier for wagons and to reduce the number of bridges and crossings soldiers would build on the rivers and streams it crossed. He kept a second journal, but the original and one known copy have been lost. It may have contained the true distance he measured by surveyor’s chain of 257 miles. The trace would become more than a mail route. Staff with History Nebraska and other historians found settlers used it when they arrived in the 1850s, and mills and towns were built at some of the crossings.

Further budget cuts to the military in 1821 reduced the troop strength at Fort Atkinson by half to 548. Field was retained and transferred to the Sixth Infantry, showing his value as an officer. He became quartermaster, a position he resigned a year later when Leavenworth refused his request to build a new storage facility. He remained at the fort, however, completing other significant assignments.

Amputation and Death

The details surrounding Gabriel Field’s untimely death are few. According to a paper by Carlson, Field was injured March 31, 1823, at Robidoux’s trading post, also known as Cabanne’s, located near what is now N.P. Dodge Park in northern Omaha. He was brought back to Fort Atkinson by boat and, on April 5, partially relieved of his duties “since illness may only be temporary.” On April 12, he was relieved of all duties, and his leg was amputated. He died on April 16.

“It has become the painful duty of the Col. Comdg to announce to his command that the gallant active and generous Lieut. Gabriel Field is no more. He died last evening at 10 o’clock in consequence of an accidental wound in the thigh with a sharp pointed knife by which the main artery and nerve were severed,” Leavenworth announced to his troops on April 17, 1823.

According to an account published in the Blair Courier in September 1890, Capt. Benjamin Contal, who lived at Fort Atkinson as a boy, said the injury was by Field’s own hand. “Lieutenant Field was playing with his knife, shutting it and throwing it one day, and it slipped and struck him in the thigh. This caused the amputation of his leg.”

The journal of another soldier also mentions the amputation. Yet military records and surgeon Gale’s log say nothing about his injury or the amputation of his leg. Jason Grof, superintendent of Fort Atkinson, and Susan Juza, a historian at the park, speculate Field had already been discharged from the military and was preparing to return to Kentucky.

Trading posts were off limits to soldiers because of the alcohol they might procure there. Yet that is where Field and Capt. Charles Pentland ended up. When Pentland showed up for roll call the next day, he had to answer to where his friend, Field, was. Court martial records from later that year show Pentland was charged with neglect of duty for leaving his post unattended. Witnesses say he was intoxicated. Field is mentioned, but nothing specific. Grof and Juza believe that is because he was a civilian and not under military law. “It’s all speculation, but I’ll say because of the place it happened, we can assume alcohol was involved,” Grof said.

Regardless of how the accident occurred or what Field’s military status was at the time, Grof and Juza aren’t surprised at the outcome. The lack of sanitation and available medical science on the frontier would have been similar to that of the Civil War era, when it is well documented that many soldiers would have survived their wounds had it not been for the infection that followed. There were no antibiotics to ward off infection, and no anesthesia to accompany the amputations that were often conducted to try and stop its spread.

“Just a shot of whiskey and a block of wood [to bite down on]” Juza said.

“Even though they amputated his leg, personally, I don’t think he would have survived,” Grof said. “Everything was stacked against him.”

Discovery of Tombstone and Remains

When Fort Atkinson was abandoned in 1827, so was the cemetery that contained the graves of the hundreds of soldiers and civilians who died there. As was the case with the fort’s structures, they had mostly deteriorated and disappeared by the time settlers began arriving in the 1850s. Soon, the town of Fort Calhoun and farm fields covered

the site.

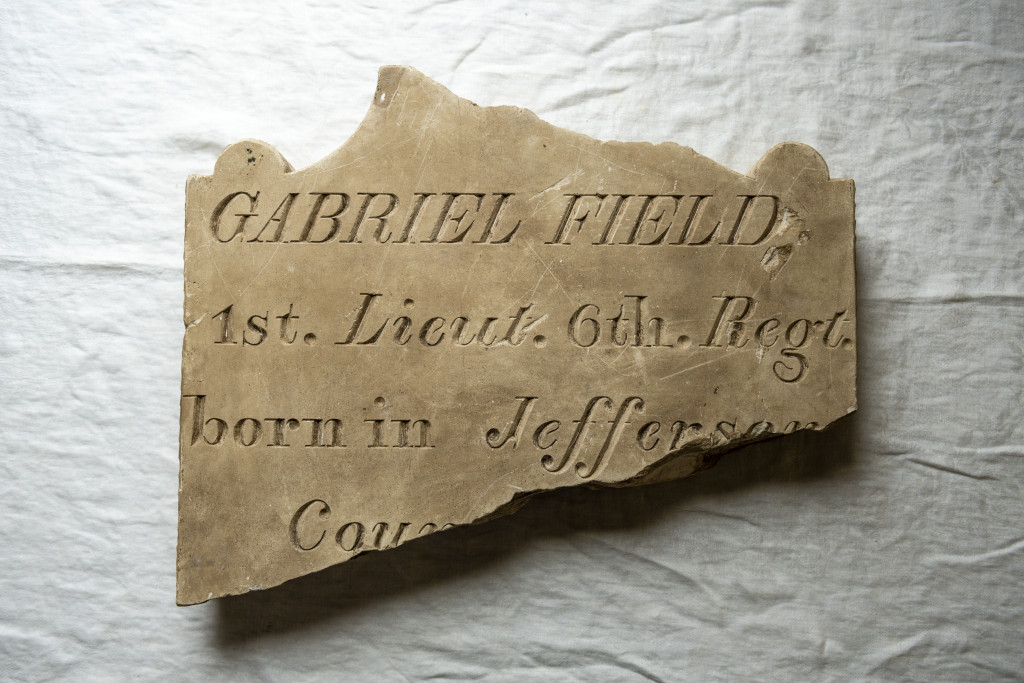

In the early 1900s, graves were found in two locations west of the fort. Portions of other headstones also were found. Jack Rathjen’s discovery of a broken piece of limestone, 16 inches wide, and 2¼ thick, inscribed with “Gabriel Field, 1st. Lieut. 6th Regt. Born in Jefferson Coun …” about one mile north of the location of the fort, however, was significant.

In 1956, Marvin Kivett, director of the state museum with History Nebraska, led an excavation at the location. In the 50-foot by 5-foot trench, they found five graves, two containing adult males, two containing children and one empty, with no artifacts to indicate the military standing of the males.

Two years later, Kivett returned after amateur archeologists uncovered another grave only feet from his earlier work. In it they found the remains of an adult male in a hexagonal coffin, the right leg having been amputated. At the foot of the grave, in a rectangular wooden box, they found the rest of that right leg. The headstone, examination of the skeleton and two historical references to Field’s amputation, however, left historians certain these remains were that of Field.

There is no record of the location of the Fort Atkinson cemetery. The location of these graves so far north of the fort, however, makes sense to historians. It is on the edge of the bluff overlooking the location of Camp Missouri, where so many died of scurvy that first winter. With so many buried, it made more sense to continue using that cemetery rather than creating a second.

Most grave markers were made of wood and lost to the elements. Because Field’s was made of limestone, “That shows how much he was liked here from his troops, the people he was stationed here with,” Grof said.

Reburied at Fort Atkinson

Bill Rathjen is the fifth generation to farm the ground north of Fort Atkinson. His great, great, grandfather, Henry Frahm, settled there in 1856. Bill was born a century later, in 1956, two years after his father, Jack Rathjen, uncovered Gabriel Field’s headstone.

He grew up hearing the stories of the area’s history, and the discovery of Field’s grave, from his father, who passed away last September. “He was always a history buff,” Bill said. “He was interested in the local history. He lived all that as a kid. He got stories from the generations before him. He loved to tell stories and he retained all that.”

Bill’s parents supported the effort to preserve the fort that began with the creation of the Fort Atkinson Foundation in 1961. The foundation and the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission purchased the property in 1963, creating Fort Atkinson State Historical Park. Bill remembers University of Nebraska students staying in tents on their farm during excavations that followed and helped guide the reconstruction of the stockade and other buildings found at the park today.

His father always hoped Field’s remains would be reburied at Fort Atkinson, Bill said. Work by Game and Parks staff to do just that began in the 1990s. In 2013, with funding provided by the foundation, the Monument to the Deceased was dedicated east of the Visitor Center. In recent years, staff followed up on previous genealogical searches conducted by Carlson to see if there were relatives of Field who might want to claim his remains. None were found in Kentucky, where Field is a common name. Other descendants were known to have lived in Ohio and Indiana. Few were found, and none knew of Gabriel Field. That cleared the way for Field’s remains, which have been housed in the archives of the Smithsonian Institution, History Nebraska and other locations for the past 65 years, to return to Fort Atkinson.

That pleases Bill Rathjen and his wife, Glenda, and would please Jack, as well, they said.

“It’s something that is important for Bill and me to pass down to our grandkids,” Glenda said. “We want them to know this story and their great-grandfather Jack’s part in it.”

Like Jack, “He was a veteran, and we need to honor our veterans,” she added.

“Dad was always concerned that he wasn’t reburied,” Bill said. “It bothered him that he was, for years, in a drawer in Lincoln and then in the Smithsonian.

“He would have been thrilled to know [Field] was going to be reburied at Fort Atkinson.” ■

A reinterment ceremony for Lieut. Gabriel Field will be held at noon, April 16, 2023, at Fort Atkinson State Historical Park in Fort Calhoun.

The post A Soldier Returns to Fort Atkinson appeared first on Nebraskaland Magazine.