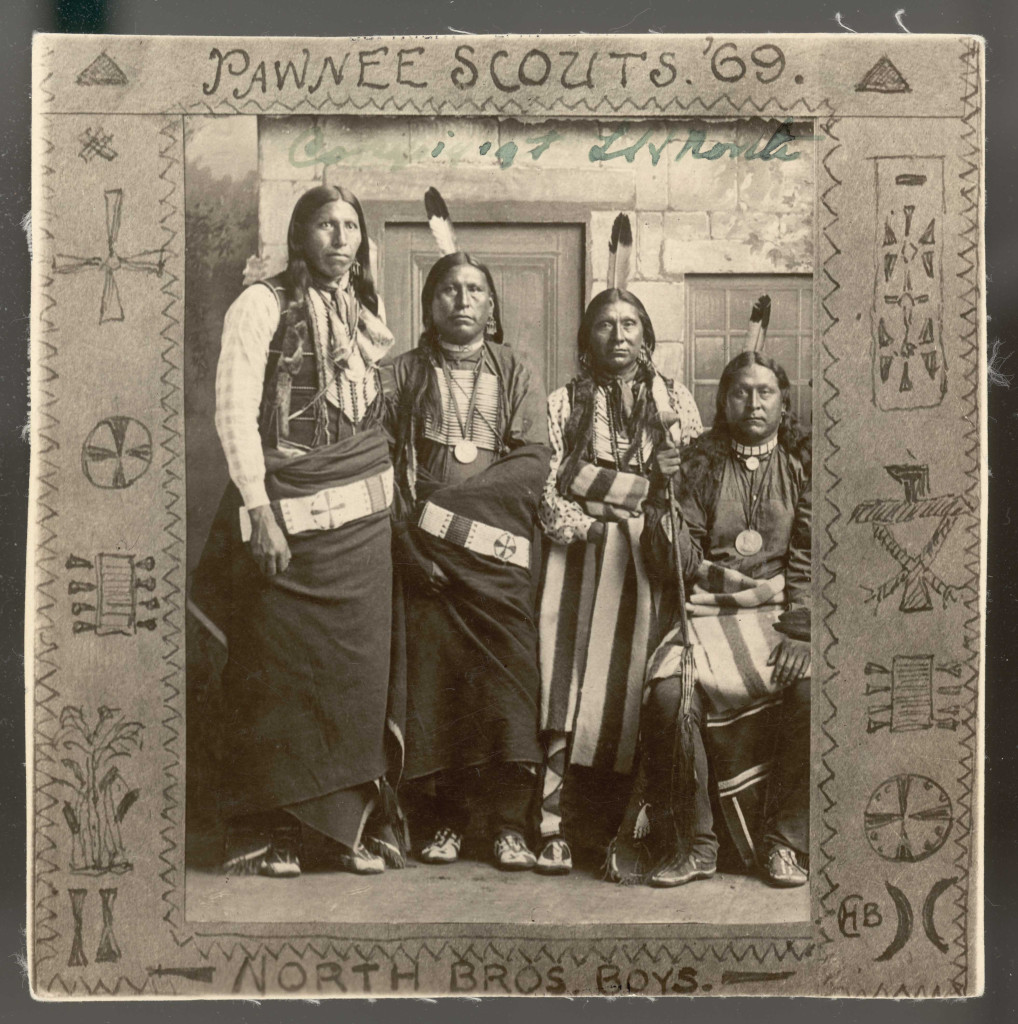

An estimated 1,000 Pawnees served as military allies of the United States between 1864 and 1877.

Enlarge

Photo by William Henry Jackson, RG2065

By Mark van de Logt

The warm summer air on July 30, 1868, was thick with bullets, arrows and the noise of charging Lakota warriors as Major Frank North sought shelter under a low cliff. Cut off from the rest of his command of Pawnee Scouts, his situation was dire.

Then, Ke wuck oo lah la shar, which translates to Fox Chief, arrived with other Pawnee Scouts.

“I found Major North and another white officer hiding under a cliff,” Fox Chief recalled many years later. “Major North told me that I had saved them when I came upon them.”

On that day, Major North, buoyed by little hostile activity that year, had taken some scouts toward the Republican River to hunt bison. While chasing the herd, he was surprised by a Lakota-Cheyenne war party. Fox Chief and his friends, who patrolled the Union Pacific Railroad between Wood River Station and Julesburg, Colorado, as part of their service, arrived just in time.

An estimated 1,000 Pawnees served as military allies of the United States between 1864 and 1877, and their military service will be honored at “The Pawnee at Fort Kearny: Share the History, Share the Harvest” on Oct. 7 at Fort Kearny State Historical Park. The 2023 harvest of Pawnee crops also will be celebrated.

Valuable Allies

Pawnee Scouts’ service was made possible by the 1866 Army Reorganization Act, which authorized the Quartermaster Department to annually enlist Native “scouts,” furnish them with guns, horses and uniforms, and pay them the same as regular troops. Fox Chief was among them; he was nearly 40 years old in February 1868 when he enlisted as a Pawnee Scout by adding his mark on the muster rolls.

“I had a bluish army suit and a black hat,” Fox Chief later recalled. “My hat had a couple of short swords across the front of it [but] I had no stripes on my pants or on my arms.”

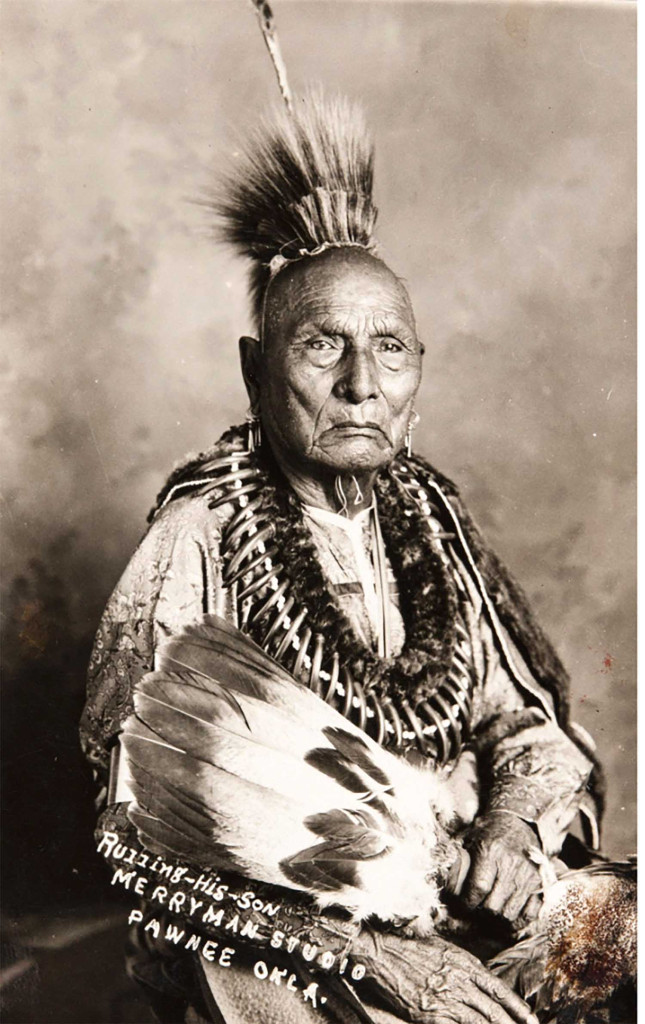

Photo courtesy of Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa OK.

The Pawnee Scouts were valuable allies because of their knowledge of terrain, familiarity with Lakota and Cheyenne military tactics, and endurance and hardiness in battle. They eventually were placed under the command of Frank North, a civilian, because he spoke the Pawnee language.

The Pawnee Battalion’s service included guarding Union Pacific Railroad workers in 1867-68, and participating in the 1865 Powder River, 1869 Republican River and 1876 Powder River campaigns. Major battles were won against the Arapaho at Tongue River in 1865, and the Cheyennes at Plum Creek in 1867 and Summit Springs in 1869.

Scouts relied on their own tactics, which utilized the element of surprise and disguise. They also practiced their own war-related ceremonies and customs while in the field. Attempts by some white officers to drill scouts like soldiers were resisted by both the scouts and North.

Individual Pawnees continued to serve as scouts at times when the battalion was inactive. They did more than guide troops through enemy territory — the scouts also spearheaded attacks against enemy encampments, carried dispatches, protected railroad workers and, on several occasions, saved military troops from disaster on the battlefield.

Not For Everyone

However, not all government officials were happy to see Pawnees in uniforms. Quaker agents believed military service hindered their efforts to create peace between Indian tribes and attempts to assimilate the Pawnees.

When the battalion was not re-activated between 1870 and 1875, the Pawnees’ enemies enacted revenge. On Aug. 5, 1873, Brule and Oglala Lakota warriors surprised nearly 400 Pawnee hunters under former Pawnee scout Ti-ra-wa-hut Re-sa-ru, or Sky Chief, near present-day Trenton.

The Pawnee warriors were greatly outnumbered, and after several hours of relentless fighting, at least 69 Pawnees lay dead. According to one account, Sky Chief killed his infant son so the baby wouldn’t be killed and mutilated by the Sioux. Sky Chief died while defending his people, and other victims at Massacre Canyon included Fox Chief’s wife and daughter.

Despite desiring revenge, Fox Chief did not sign up for the 1876 campaign that culminated in the “Dull Knife Fight,” during which the Pawnee Scouts and their U.S. allies inflicted a decisive defeat on the Cheyennes. Perhaps he wished to enlist, but Major North rejected him due to his advanced age.

Disbanded

When the Pawnee Battalion was disbanded in 1877, the United States soon forgot the scouts’ sacrifices. Many scouts struggled to get government pensions for their military service. That included Fox Chief, whose name was changed after moving to Oklahoma in 1873. People began calling him Ruling His Sun; by 1928, Ruling His Sun couldn’t remember who gave him that name and, by then, most Pawnees called him Osage.

The name confusion frustrated his attempt to secure a military pension. It took a special act from Congress to grant him a $20-a-month pension in 1924. The rate increased to $50 shortly before he died on Oct. 4, 1928, at nearly 100 years old.

Ruling His Sun remained fiercely proud of his Pawnee and scout heritage. In 1925, despite his age, he had to be restrained from fighting several Lakota delegates at the anniversary of the tragedy at Massacre Canyon.

Today, the Pawnee people remember him and fellow raaripákusu’ as the first Pawnee-American patriots.

Mark van de Logt is an associate professor of history at Texas A&M University at Qatar and author of “War Party in Blue, Pawnee Scouts in the U.S. Army.”

Event Information

On Oct. 7 from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., Fort Kearny State Historical Park and Fort Kearny State Recreation Area will host the “Share the History, Share the Harvest” event honoring the estimated 1,000 Pawnees who served as U.S. military allies from 1864-1877. There is no admission fee, but a Nebraska State Park entry permit is required at both sites.

The post A History of the Pawnee Scouts appeared first on Nebraskaland Magazine.